News

The latest news about everything happening in the Salzburg Mozarteum Foundation around Mozart Week, Season concerts, the Mozart Museums and the research about Mozart.

Three new Mozart letters in Salzburg

The Salzburg Mozarteum Foundation announces three important acquisitions, including the last letter that Mozart wrote to his father in April 1787

At the beginning of 2020, before the coronavirus pandemic became a pressing concern, a courier arrived in Salzburg from the United States of America. The Mozart Week Festival was in full swing at the time. He had in his possession three letters written by members of the Mozart family that undoubtedly is the most important addition to the collection of original letters held by the Salzburg Mozarteum Foundation in recent decades. As a result of the current pandemic, we were able to post only one of these letters online on Good Friday as part of our #kleinePauseMozart page. This letter was addressed by Mozart to his “dearest, most treasured little wife” and was written to her from Prague during his journey to Berlin, Dresden and Leipzig in 1789. This was the first time that the Mozarteum Foundation had been able to acquire one of the extremely rare letters that Mozart wrote to Constanze on his travels during the final years of his life.

The second letter was written in Bologna on 28 July 1770 during the Mozarts first visit to Italy and perfectly fits into the Foundation’s extensive collections. The main body of this substantial letter was written by Leopold Mozart to his wife Anna Maria, who had remained behind in Salzburg, but it also includes a short postscript by Wolfgang Amadé Mozart, written in Italian and addressed to his “carissima sorella” (dearest sister), Maria Anna (“Nannerl”). This letter is particularly important from a historical point of view since it provides us with a detailed account of the prestigious commission that required Mozart to compose the first opera for the 1770–71 Carnival season in Milan. This is the first time that we learn not only the work’s title, “Mitridate, re di Ponto”, but also the names of the librettist and of the singers who would be involved in the production. Two of them, Guglielmo d’Ettore and Antonia Bernasconi, were among the most acclaimed opera singers of their day.

But the most important of these new acquisitions is the touching letter that Mozart wrote to his father on 4 April 1787 after he had learnt that Leopold was seriously ill – by 28 May his father was dead. It contains the famous lines: “death | : when looked at closely : | is the true goal of our lives, and so for a number of years I’ve familiarized myself with this true best friend of man to such an extent that his image is not only no longer a source of terror to me but offers much that is comforting and consoling! – And I give thanks to my God that He has given me the good fortune of finding an opportunity | : you under-stand what I mean : | of realizing that death is the key to our true happiness. –”

Like so many of the letters that Mozart wrote to his father from Vienna, this one begins with an apology, on this occasion for the fact that the mother of Nancy Storace – Mozart’s first Susanna in “Le nozze di Figaro” – had forgotten to give Leopold a letter from his son on her way from Vienna to London, where Nancy had just been offered a contract at the King’s Theatre. The next section of this letter of 4 April 1787 is given over to musical gossip: several mutual friends and acquaintances had visited Vienna during Lent, among them the German oboist and composer Johann Christian Fischer, whom the Mozarts had got to know while visiting the Netherlands in 1765–66. But Mozart now sought to distance himself from his childhood memories: Fischer not only played in an old-fashioned way but had poor intonation and lacked musical taste. The tone of Mozart’s letter suddenly becomes more serious at this point, and he goes on to explain that he has just heard from a third party that in spite of Leopold’s repeated assurances to the contrary, his father is gravely ill.

He longs to receive reassuring news from Salzburg. This is followed by the famous phrases and thoughts about death that we quoted above. Here Mozart refers to the unexpected death of his “dearest and best friend”, Count August Clemens von Hatzfeld, who had recently died at the age of only thirty-one and whose passing had evidently affected Mozart deeply. Mozart ends his letter by begging his father to tell him the truth about his state of health: “I hope and pray that, even as I write these lines, you’re feeling better; but if, contrary to all expectations, you’re not better, I would ask you by …… not to hide this from me but to tell me the plain truth or get someone to write to me, so that I may hold you in my arms as fast as is humanly possible; I entreat you by all that’s sacred to you.”

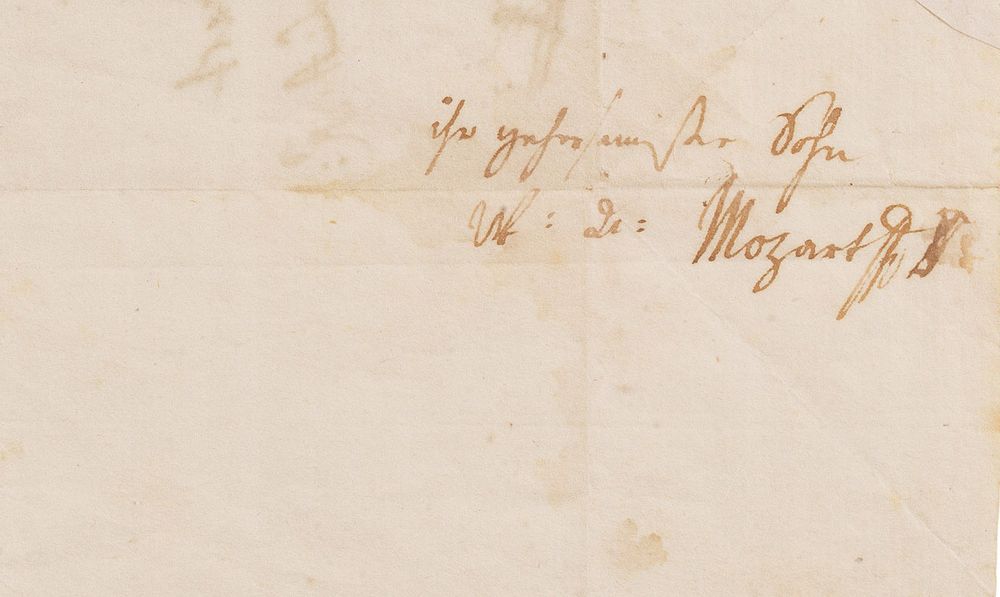

This letter is influenced by the spirit of Freemasonry, a movement to which Mozart felt deeply committed. Indeed, he had even introduced Leopold to its rituals during his father’s visit to Vienna in 1785. This assumption is supported by the references to friendship and philanthropy implied by Mozart’s statement that death is “the true best friend of man”. But there is further evidence in the somewhat indistinct symbol that Mozart exceptionally added to his signature, following the abbreviation “m.p.” (manu propria = in his own hand) with a sign that may be interpreted as two interlocking triangles. This same symbol also occurs, for example, in Leopold’s “Masonic” letter of 8 July 1785 as well as in Mozart’s entry in the album of a fellow lodge member dated 30 March 1787, less than a week before his letter to his father.

The contents of all three letters have been known since the nineteenth century, but for a long time the holographs have not been accessible – in the case of Mozart’s letter to his father, for example the document was in private hands during the last 90 years and had not even been photographed. These newly acquired letters have already been integrated into the Mozarteum Foundation’s digital edition of the Mozart family letters both as images and as up-to-date transcriptions. All the Mozart family’s surviving letter from the years between 1755 and 1791 are already freely accessible as part of the Foundation’s Digital Mozart Edition, where they may be consulted for private, scholarly and teaching purposes. Here are links to all three letters:

* Letter from Leopold Mozart to his wife Anna Maria (Bologna, 28 July 1770)

* Letter from Wolfgang Amadé Mozart to his father Leopold (Vienna, 4 April 1787)

* Letter from Wolfgang Amadé Mozart to his wife Constanze (Prague, 10 April 1789)

A high-quality facsimile of Mozart’s letter to his father may be bought from either of the Mozarteum Foundation’s two museums, namely, the house where the composer was born and the family residence on the Makartplatz. It is also available online at https://www.mozarthaus.biz at € 10.95 (ISBN 978-3-901955-15-0).

The Salzburg Mozarteum Foundation owns the world’s largest collection of Mozart family letters, most of which have been in Salzburg since the middle of the nineteenth century, when Mozart’s two surviving sons, Carl Thomas and Franz Xaver, bequeathed all the originals in their possession to the Cathedral Music Society and Mozarteum, the immediate predecessor of the Mozarteum Foundation. But Mozart’s letters to his wife Constanze were not a part of this bequest, Constanze and her two sons often gave away particularly valuable documents to friends and Mozart enthusiasts while they were still alive. The three letters that have recently been acquired by the Mozarteum Foundation had all gone their separate ways in the nineteenth century but with the support of the W. A. Mozart Foundation of Switzerland and through the intermediary of the London-based auctioneer Stephen Roe they have now been bought for a six-figure sum from the estate of the American writer and book illustrator Maurice Sendak (1928–2012). The price paid represents the letters’ current value. The Mozarteum Foundation is extremely grateful to the letters’ previous owner for offering them to us directly. Both parties have agreed not to divulge the exact price that was paid.

According to the Foundation’s president, Johannes Honsig-Erlenburg, “Although we have been fortunate to have been able to add a number of items to our collection of autograph documents in recent years, I find myself particularly affected by Mozart’s last letter to his father, which is unusually profound and thoughtful. Only the original, with its easily overlooked symbols, reveals what generations of Mozart scholars have suspected, namely, that this letter was powerfully influenced by Masonic ideals. In this way it is not as a son that Wolfgang Amadé Mozart bids farewell to his father but as one brother to another. What a deeply touching moment this is, and one in which we can now all participate!”