Wolfgang Amadé Mozart

1756–1766: Child prodigy years

Wolfgang Amadé Mozart (baptised Johannes Chrysostomus Wolfgang Theophilus) was born on 27 January 1756, seventh and last child of Salzburg court musician Leopold Mozart (1719–1787) and his wife Anna Maria, née Pertl (1720–1778). His only surviving sibling was his sister Maria Anna, called Nannerl (1751–1829), five years his senior. At the age of five or six, Wolfgang demonstrated his outstanding talent at the courts of Salzburg, Munich and Vienna. His success encouraged Leopold to undertake an extensive concert tour, with both children performing, and Wolfgang increasingly presenting his own compositions. Between June 1763 and December 1766, their journey included Paris, London, The Hague, southern and western Germany and Switzerland.

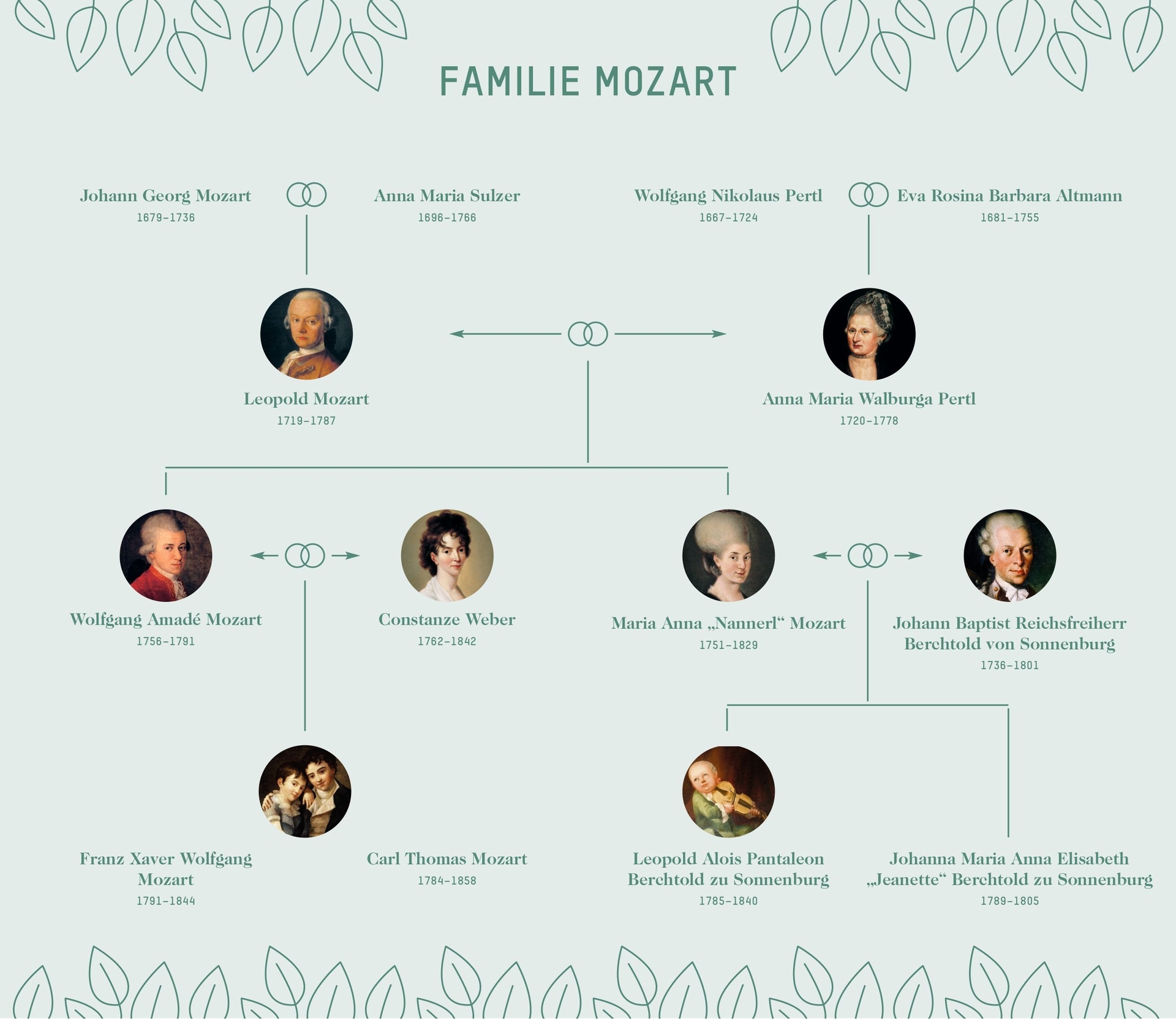

Mozart family tree

Leopold Mozart and Anna Maria had seven children, five of whom did not survive infancy.

Maria Anna (“Nannerl”) lived from 1751 to 1829. Two children were born of her marriage with Johann Baptist Franz von Berchthold zu Sonnenburg.

Wolfgang Amadé Mozart was born on 27 January 1756. Two sons were born of his marriage with Constanze Weber (1762 – 1842). Wolfgang Amadé Mozart died at the age of 35 on 5 December 1791.

The Mozart family

Wolfgang Amadé Mozart came from a very musical family. At a very early age, he and his sister received music tuition from their father, himself a composer. The family was considered well-to-do.

The Mozarteum Foundation has a considerable part of the correspondence between Wolfgang and his family, which gives details about the relationship between the family members as well as about Mozart’s work.

Leopold Mozart was unquestionably one of the most interesting and versatile personalities of his day: productive composer, long-serving court musician and violinist, vice-kapellmeister, skilful music engraver, music copyist, successful teacher, intelligent tutor and promoter of his talented children, respected writer and scholar, attentive observer, excellent letter-writer, affectionate husband and caring, sometimes didactic father, convivial host, cultured reader, art-lover and collector, keen theatre- and opera-goer, clever networker, single-minded organiser, prudent travel manager and concert organiser, devout Catholic, Freemason, provocative subject, free spirit and man of the Enlightenment, supporter of musicians’ widows.

Leopold Mozart was born in Augsburg on 14 November 1719, and baptised the same day in St George’s Church. He was the eldest son of master bookbinder Johann Georg Mozart and his wife Anna Maria, née Sulzer. As a boy, Leopold received a sound humanist education at St Salvator’s Jesuit college, possibly with the aim of studying theology, and probably learned there to play violin and organ. A few months after his father’s death in 1736, he left his home town for Salzburg, to study at the Faculty of Philosophy of the Benedictine University. After less than two years, however, he was expelled for poor attendance.

He found a patron in Count Johann Baptist of Thurn-Valsassina and Taxis, who employed him as a valet and violinist. In 1743 Leopold Mozart became a member of the Salzburg court orchestra, rising to the post of second violinist (1758) and finally to that of vice-kapellmeister (1763).

He married Anna Maria Pertl in 1747, and they lived on the Löchelplatz, on the third floor of the Hagenauer house (now Getreidegasse 9), where their seven children were born, only two of whom – Maria Anna, called Nannerl, and Wolfgang Amadé – survived. In the autumn of 1773 the family moved to the Tanzmeisterhaus [dancing-master’s house] on Hannibalplatz (now Mozart residence, Makartplatz 8).

Leopold Mozart was not only a devoted husband and father, but was held by his contemporaries in high regard as a composer and music teacher, as well as a widely-cultured and convivial personality. His treatise on violin-playing (1756) brought him Europe-wide fame, which has lasted to the present day.

Anna Maria Walburga Pertl was born in St. Gilgen am Wolfgangsee on 25 December 1720, daughter of Wolfgang Nikolaus Pertl, an official at the archiepiscopal court. After the premature death of her father, she moved to Salzburg with her mother and her elder sister, who died shortly afterwards. Until her marriage to court violinist Leopold Mozart in November 1747, she lived in humble circumstances, dependent on a charity pension granted by the Archbishop.

In the first nine years of her marriage she bore seven children, only two of whom reached adulthood. These two, Maria Anna (Nannerl) and Wolfgang Amadé, five years her junior, were to have a decisive influence on her life.

Due to her husband’s professional advancement and his tireless work in training and promoting the development of their talented children, Anna Maria Mozart’s life was shaped by travels through Europe, by music, art and culture, and by encounters with crowned heads and members of the highest aristocracy. She could read and write – not a matter of course for a woman at that time. When Leopold took Wolfgang to Italy, he entrusted various tasks to her, such as the sale of his violin tutor, which was in demand all over Europe.

Like her daughter, Anna Maria Mozart liked fashionable clothes and accessories, and of course she took part in all the domestic entertainments such as card-playing and Bölzlschiessen [target-shooting].

She ensured the smooth running of the household and a harmonious family life, her calm humour keeping an equable atmosphere even in difficult situations. With much tact and understanding, she managed to mediate between her sometimes pigheaded husband and their brilliant but fanciful son Wolfgang Amadé.

Their marriage may be regarded as a love match; in Salzburg, Anna Maria and Leopold were considered “the handsomest married couple”. Leopold always spoke affectionately about his wife, “the most honest woman and best of mothers”. He once wrote to his son: “Your dear blessed mother was well-known from her childhood and loved everywhere, because she was kind to everybody and never insulted anyone.”

There are few self-testimonies from Anna Maria Mozart. Her only surviving letters date from the last year of her life, from her journey with her son to Mannheim and Paris in 1777/78 – a journey from which she would not return. She died in Paris, after a brief illness, on 3 July 1778, at the age of 57.

Maria Anna Walpurga Ignatia (Nannerl) Mozart was born in Salzburg during the night of 30/31 July 1751, the fourth (and first surviving) child of court violinist Leopold Mozart (1719-1787) and his wife Anna Maria Walpurga (née Pertl, 1720-1778).

Aged eight, Maria Anna received piano tuition from her father, which proved an inspiration for her brother Wolfgang, five years her junior. The “Nannerl-Notenbuch”, started by Leopold in 1759, served both children as a piano tutor, later including Wolfgang’s early compositions.

Between 1762 and 1768, the whole family travelled through much of western Europe, often staying in Vienna. Leopold tutored both children professionally, giving them a good general education and a knowledge of foreign languages. During these travels, both child prodigies gave musical performances, mainly on the piano.

Mozart’s elder sister was a talented pianist who could master even the most difficult of her brother’s compositions. She was in demand as a piano teacher in Salzburg, and as an adult she still performed in public concerts. Although her father and brother tried to encourage her, she composed only little, and regrettably, none of these pieces has survived.

Constanze Mozart (née Weber, by second marriage Nissen) died in Salzburg on 6 March 1842, aged 80. She was married to Wolfgang Amadé Mozart from 1782 until his death in 1791.

Constanze Mozart, whose elder sisters Aloysia and Josepha were professional singers, was also musically talented. She sang and played the piano, though only privately during her first husband’s lifetime, apart from her participation in his C minor Mass at St Peter’s Church in Salzburg, in October 1783. In 1795/96 she undertook an extensive concert tour with her sister Aloysia as far as Hamburg, singing works by Mozart in public benefit concerts for self-promotion.

In August 1824, Constanze, now married to Georg Nikolaus Nissen, came to Salzburg where she lived until her death. Here she set to work on completing the first comprehensive biography of Mozart, which Nissen had left unfinished at his death in 1826. The book was published at the beginning of 1829.

Later, she also supported the erection of the Mozart monument in Salzburg, and founded the Cathedral Music Society and Mozarteum, donating money, books, a valuable Mozart autograph and various printed copies of sheet music.

Constanze received visits in Salzburg from many admirers of Mozart, including Italian opera composer Gaspare Spontini, English composer Vincent Novello and his wife, and German violinist Louis Spohr.

Her funeral ceremony in St Sebastian’s Cemetery on 8 March 1842 was attended by representatives of the town, members of the monument committee and of the Cathedral Music Society and Mozarteum. The following day, her first husband’s Requiem was performed in her honour in St Sebastian’s Church.

Carl Thomas Mozart was born in Vienna on 21 September 1784, second of seven children of Wolfgang Amadé Mozart and his wife Constanze, née Weber. Only he and his younger brother Franz Xaver Wolfgang, seven years his junior, survived childhood. After his father’s death, he was brought up by friends in Prague between 1792 and 1797. At the age of only 13, he left for Livorno (then still in the Habsburg Duchy of Tuscany), where he was apprenticed to a trading firm. He moved to Milan in 1805 to study music, but abandoned this course in 1810 to become a translator, working in the government accounting department.

Together with his brother, Carl Thomas took part in the celebrations for the erection of the Mozart monument in Salzburg in 1842; both of them, through donations and bequests (including the family correspondence), supported the activities of the Cathedral Music Society and Mozarteum, the predecessor of the Salzburg Mozarteum Foundation.

Important legacies from Carl Thomas, who died without issue on 31 October 1858, were Mozart’s original hammerklavier [fortepiano] and most of the original portraits of members of the Mozart family.

Franz Xaver Carl Thomas Mozart was born in Vienna on 26 July 1791, last of seven children of Wolfgang Amadé Mozart and his wife Constanze, née Weber. Following his father’s death, he remained in Vienna, then from 1795, like his brother, he was brought up in Prague for several years. His mother Constanze and her friend – later second husband – Georg Nikolaus Nissen destined him for a career in music, and from around 1800 he trained in piano and composition with the best masters in Vienna, including Sigismund Neukomm, Johann Andreas Streicher and Antonio Salieri. At the age of only 16 , he eluded the increasing pressure to become a second Wolfgang Amadé Mozart, by accepting a position as a private music teacher in Pidkamin (Galicia, now Ukraine). From 1813 he worked as a freelance musician in Lviv, where he remained until 1838, apart from a major concert tour lasting from 1819 to 1821. He spent his final years in Vienna, and died unmarried on 29 July 1844 while taking a cure in Karlsbad for stomach problems.

Franz Xaver Mozart was a concert pianist of some repute. He also composed, mainly piano music and lieder, most of his works dating from between 1804 and about 1822. He bequeathed the clavichord and many autograph fragments of his father’s, together with his own music library, to the Cathedral Music Society and Mozarteum in Salzburg; his friend and universal heir Josephine Baroni-Cavalcabò later donated the majority of his own compositions to the Society.

fun-facts-in-videos

Mozart’s life, though short, is very rich in exciting stories and amusing anecdotes. We have picked up some of them and staged them as short videos.

The great Mozart operas

Mozart wrote 22 stage works, the most famous including the Da Ponte series (Le Nozze di Figaro, Così fan tutte and Don Giovanni) and Die Zauberflöte [The Magic Flute], which was premièred shortly before his death.

Idomeneo K366 is considered the first of the “seven great operas” by Wolfgang Amadé Mozart. Composed during the autumn and winter of 1780 in Salzburg and Munich, it was premièred in the Cuvilliés-Theater in Munich on 29 January 1781, two days after Mozart’s 25th birthday. Mozart himself conducted the first performances from the harpsichord; in order to read the bass line more easily in the dark opera house, he wrote it large and clear in his score.

Idomeneo was Mozart’s favourite of all his operas – but it was performed only once again during his lifetime, as an amateur performance in Vienna, in March 1786.

The end of Wolfgang’s last visit to Salzburg, in October 1783, was marked by a tearful farewell, when his father, sister and wife joined him in singing the quartet “Andró ramingo” from Idomeneo, in which Prince Idamante takes leave of his father Idomeneo, his beloved Ilia and her rival Elettra, before going to battle the sea monster that threatened Crete – to bring victory for his fatherland, or die.

The crux of the plot is criticism of the arbitrary rule of the aristocracy. As a proponent of enlightened absolutism, Emperor Joseph II was in favour of restricting the privileges of the aristocracy. So the opera was in fact well-timed for him, calling attention to social injustices and tackling them.

The work is not critical of the Enlightenment idea pursued by Joseph II. On the contrary – Joseph II saw theatre as a moral institution, as a “school of manners” (with no political connotations) for the people. Any breaches of propriety or public morality, however, were strictly forbidden. Suggestive roles, allusions or morally reprehensible scenes were prohibited on the stage, since the purpose of theatre was to “educate” the people.

Johann Rautenstrauch made a German translation of Beaumarchais’s comedy La folle journée ou le mariage de Figaro for Schikaneder’s theatre troupe. Like the French original, the German version contained many suggestive allusions, and was therefore printed only as a book for the cultured classes, but not authorised as a play for the common people, since this would have contradicted the idea of the theatre as a school of manners. With their poetic and musical adaptation of the play for an Italian opera, Da Ponte and Mozart managed to veil all the double entendres and obscenities in the original text so cleverly that these were no longer obvious, and – unlike the play staged by Schikaneder – the opera passed the Emperor’s censorship.

In the age of the Enlightenment, the ius primae noctis (the supposed feudal right of a lord to sleep with the bride of one of his subjects on her wedding night) was frowned upon. Count Almaviva has abolished this custom in his domain, but is not prepared to observe his own rule. His servant Figaro is about to marry Susanna, the Countess’s maid, and the Count wants to spend the wedding night with her. In order to thwart this plan, the Countess and Susanna devise a ruse: Susanna will pretend to yield to the Count’s advances and invite him to a rendezvous; but it is really the Countess, disguised as Susanna, who will meet him. When Figaro learns of Susanna’s invitation to the Count, he doubts her fidelity, swears revenge and vows to confront her at the rendezvous. In the garden at night, the Count pays court to the supposed Susanna (actually the Countess), saying how beautiful she is and how soft her skin, and he gives her a ring. Figaro also enters the garden, intending to catch his bride in flagranti with the Count and expose her infidelity. In order to punish Figaro for his jealousy and lack of trust, Susanna appears, disguised as the Countess – but unlike the Count, who has not recognised his own wife, Figaro immediately sees through Susanna’s disguise. He pretends to believe she is the Countess and starts paying court to her. She soon realises the truth, and having made peace, they decide to carry on play-acting in order to fool the Count, Figaro openly flirting with the supposed Countess. The Count, beside himself with jealousy, roars that his wife is deceiving him – whereupon the Countess reveals herself, and the Count, humbled, is forced to apologise to her. She accepts, and the nocturnal revels in the garden can continue.

Pasquale Bondini, director of the opera in Prague, had a keen instinct for what would work well on the stage. Only a few months after its Vienna première, he put on Mozart’s Le nozze di Figaro, which was such a success that he invited the composer to Prague to conduct the work himself. During this visit at the beginning of 1787, Bondini also commissioned a new opera which – though no-one would have guessed this at the time – was to be an even greater triumph. Mozart and his librettist Lorenzo Da Ponte chose the “timeless” Don Juan story, which had frequently been staged as both play and opera since the 17th century.

The première was planned for 14 October 1787, to honour Archduchess Maria Theresia Josepha of Austria and her husband Anton von Sachsen, staying in Prague on their way to Dresden. However, in a letter to his Viennese friend Gottfried von Jacquin, dated 15 October, Mozart wrote: “You will probably believe, sir, that my opera is already over – yet in that you err somewhat. First of all, the theatre personnel are not as skilful here as in Vienna, as would be necessary to rehearse such an opera in this short time. Secondly, I found so few preparations and arrangements on my arrival here that it would have been a sheer impossibility to give [the work] on the 14th, which was yesterday. So instead, they put on my Figaro, which I conducted myself, in the fully illuminated theatre.”

Don Giovanni was finally premièred fourteen days later, on 29 October 1787, in the Count Nostitz National Theatre in Prague.

Don Giovanni is the second opera, after Le nozze di Figaro, in which Mozart collaborated with Lorenzo Da Ponte; there followed Così fan tutte in 1790. Despite the sombre scenes, Mozart and Da Ponte saw Il dissoluto punito ossia Il Don Giovanni as a dramma giocoso; in his autograph catalogue of works, Mozart even entered Don Giovanni as an opera buffa. In comparison with Figaro, the music is in many places darker, more dramatic and sepulchral. Unusually for an opera buffa, the overture begins in D minor, anticipating the end awaiting the “punished profligate”. Mozart is said to have written the overture in a single night, only a few days before the première.

In the Romantic period, Don Giovanni was regarded as the epitome of Mozart’s operas, and today it is even more popular – not only with musicians, but also with audiences.

Our Online-Edition of the Mozart letters and documents contains the whole letter from Mozart to Gottfried von Jacquin.

The score is available in the NMA Online under K 527 or under the search term “Don Giovanni”.

Further details, for instance the first edition of the score (1801), are available in our digital library.

Così fan tutte K 588 was premièred in the “old” Burgtheater on the Michaelerplatz in Vienna on 26 January 1790. The libretto was once again by Lorenzo Da Ponte; this was to be the last time Da Ponte would write a libretto for a Mozart opera.

1789/90 were very mixed years for Mozart and his wife. Constanze suffered poor health; she needed courses of spa treatment, which cost money – money that Mozart did not have. More than once during this period, he had to ask his friend Johann Michael Puchberg to lend him some. At last, however, he received a further opera commission in Vienna, probably from Emperor Joseph II, and the result was Così fan tutte o sia La scuola degli amanti [All women do it, or the school for lovers].

The plot concerns two young officers, Ferrando and Guglielmo, who are induced by the cynical older Don Alfonso to bet on the fidelity of their betrothed, Dorabella and Fiordiligi. Soon the two officers are ostensibly called away to war, and they return disguised as Albanian noblemen who wish to court the girls. The supposed foreign gallants pay court to the sisters, but to the amazement and initial relief of the two men, the girls remain steadfast, ignoring all the foreigners’ blandishments. So the spurned lovers renew the attack with heavier artillery, and pretend to take poison since their love is unrequited. They are revived by the maid Despina, disguised as a doctor, who entrusts them to the care of the two sisters …

Mozart himself conducted the first performances of Così fan tutte in Vienna. It was customary at the time for a composer to conduct at least the first performances of a commissioned work. In a letter written in 1790 to his friend Johann Michael Puchberg, Mozart reported:

“Dearest friend… I am here to conduct my opera. My wife is slightly improved. – She is already feeling some relief, but she will have to bathe 60 times – and will have to go out again in autumn […]”

The whole letter is available here: Letter dated June 1790 to Johann Michael Puchberg .

The libretto is available here: Libretto of Così fan tutte K588.

Link to the NMA Online [New Mozart Edition] where the opera can be watched and heard.

Further details about Mozart’s operas are given in the Digital Mozart Edition.

On 30 September 1791, The Magic Flute was premièred in a suburban Viennese theatre, the Freihaus-Theater auf der Wieden, which had been leased since 1789 to the glamorous opera impresario Emanuel Schikaneder. Mozart and Schikaneder had first met in 1780 in Salzburg, where the latter was staying for a few months, on tour with his travelling troupe. With its fairytale action, markedly shaped by Freemasonic ideas, The Magic Flute belongs to a repertoire of comic Singspiele extremely popular at the time but now completely forgotten. The première was originally planned for the summer of 1791; Mozart entered the work in his autograph catalogue in July. But then the prestigious commission for the festive opera La clemenza di Tito in Prague supervened; it was premièred there on 5 September 1791 for the coronation celebrations of Leopold II. Not until his return from Prague did Mozart write the music for the priests’ march in Act II and the overture to The Magic Flute. As was customary, he himself conducted the first performances from the keyboard; his sister-in-law Josepha Hofer sang the Queen of the Night, and Schikaneder played Papageno (frequently improvising new lines). Pamina was sung by Anna Gottlieb, who had played Barbarina in Figaro five years previously, at the age of only twelve. Mozart attended almost all the further performances with friends and relatives, until he fell seriously ill in mid-November and died on 5 December 1791.

The outstanding quality of the music made The Magic Flute a sensational success. Schikaneder and his troupe alone performed it no less than 223 times, until a new building, the Theater an der Wien, opened in 1801. Within a few years, the opera had reached the entire German-speaking, and soon the entire musical, world – and today it is still one of the most-performed operas worldwide.

The archive of the Mozarteum Foundation contains many stage-set design models for The Magic Flute.

The marriage of Wolfgang and Constanze

Mozart and Constanze Weber first met in 1777 in Mannheim, then Rhineland-Palatinate (now Baden-Württemberg). Initially, Mozart had fallen in love with Constanze’s sister Aloysia, eldest daughter of the Weber family of musicians from the Black Forest town of Zell im Wiesental. In 1781, he once again encountered the family , who had moved to Vienna. His adored Aloysia had in the meantime met and married another man, court actor and painter Joseph Lange. Mozart stayed with the family in Vienna for a time, during which he and Constanze grew closer, and the following year they married in St Stephen’s Cathedral in Vienna. Their happy marriage and partnership, marked by love and mutual respect, lasted until Mozart’s death. Many letters testify to Wolfgang’s great love for his wife.

In 1799, Constanze herself admitted openly to the Leipzig publisher Breitkopf & Härtel that it was Mozart’s many letters to his “dearest, best little wife” during their final years together that express “his abundant tenderness for me”. Thirty years later, now twice widowed, she wrote to Friedrich Schwaan, Rostock music teacher and admirer of Mozart:

“I have had two most excellent husbands by whom I was loved and honoured – even, I have to say, adored; they, too were both equally loved by me with the utmost tenderness, thus I was twice completely happy.” (Letter dated 5 December 1829)

Mozart's death

There are many myths and legends about Mozart’s death on 5 December 1791, since only few facts are established with certainty through documents. Researchers are still puzzling over the exact cause of his death, but they are all agreed that it was not poison.

The entry in the coroner’s report by his personal physician Dr. Closset stated that Wolfgang Amadé Mozart died on 5 December 1791 of “hitzigem Frieselfieber” [acute miliary fever]; this is not a precise medical diagnosis, but was in keeping with the official ordinance requiring a “brief notation of the manner of death” in the German language (i.e. not in Latin). For over 200 years, medical specialists have been attempting to determine the actual fatal illness, by means of contemporary accounts of the symptoms and the course of the disease (often written down much later) – with different results.

Also according to later reports, Mozart was consecrated in his coffin on 6 December 1791 at about 3 pm in front of the so-called Crucifix Chapel on the north side of St Stephen’s Cathedral. That same evening he was taken to St Marx cemetery, in a suburb of Vienna some 4 km away. An ordinance forbade mourners to follow the hearse beyond the town boundary.

Like many contemporaries of similar status, Mozart was given a third-class funeral, as entered in the register of deaths of the Cathedral Parish of St Stephen under 6 December 1791. The costs were fixed according to surplice fees. Mozart was buried in an unmarked shaft grave (usually a grave with four or five other bodies); this was common at the time, and was not (as sometimes asserted) a “pauper’s burial”.

St Marx Cemetery was closed in 1874 and is now a public park. The Mozart monument erected there in 1859 was moved in 1891 to the main cemetery (Zentralfriedhof) to join the group of Ehrengräber [graves of honour]. Mozart’s grave in St Marx, a pilgrimage site for many visitors today, was later marked by a cemetery-keeper, who used materials left over from other graves, so that Mozart could be remembered at the abandoned site. It is located on the site of the former shaft graves.